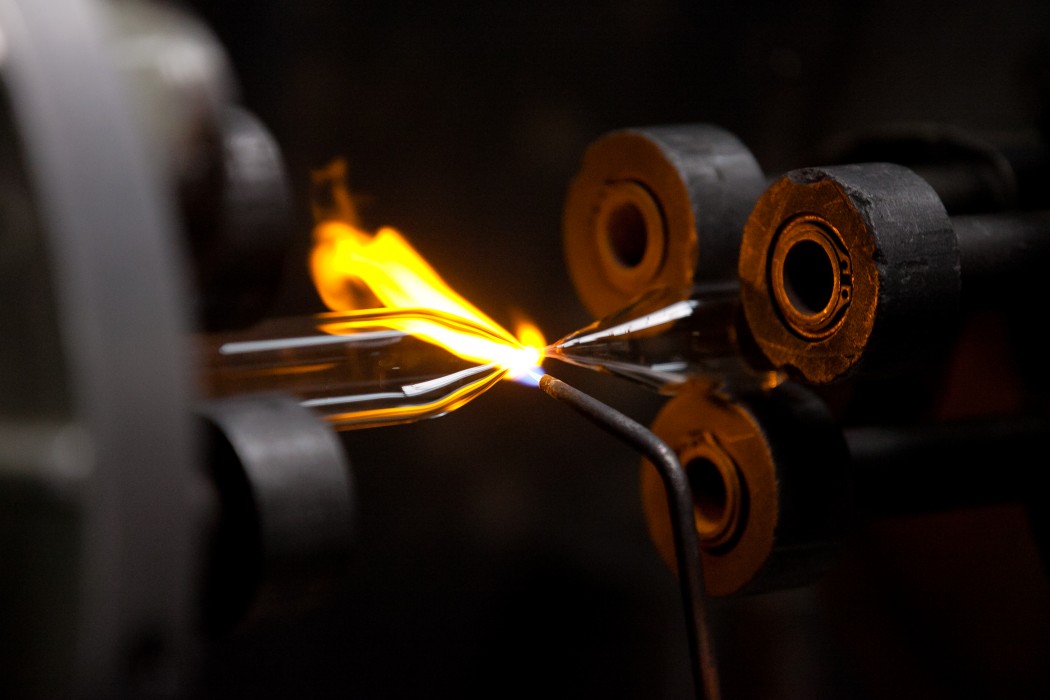

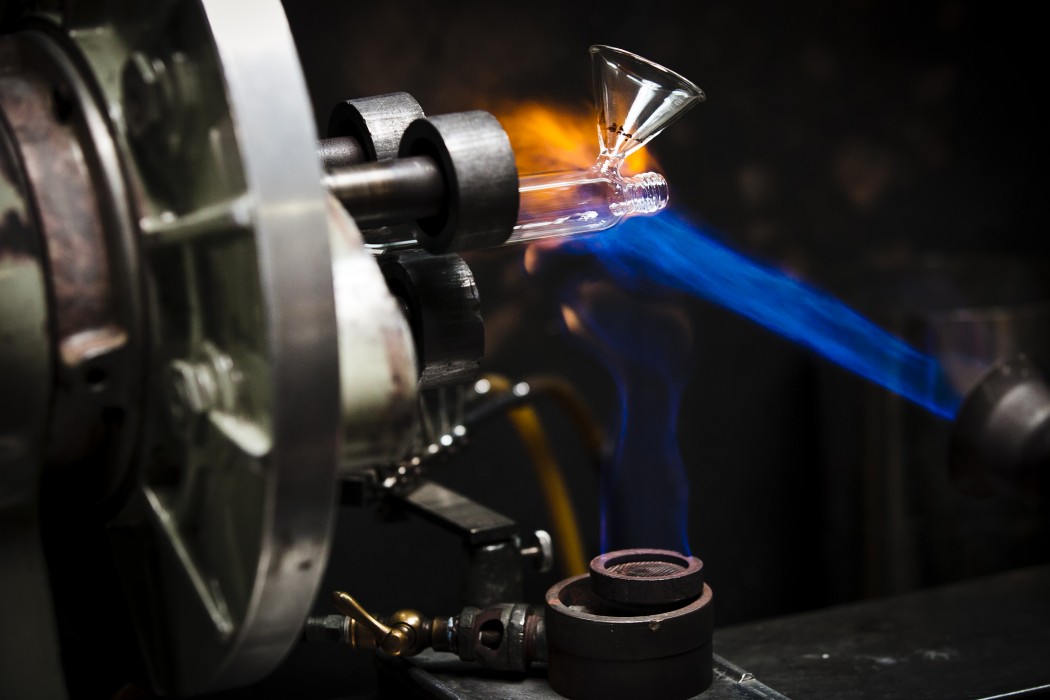

Photographs from 2012 residency.

Location: San Francisco Center for the Book

Photography: Heimo

The term Wunderkammer, often translated as “room of wonder,” is exactingly literal, as is so often the case with German nouns. The word manages to lower expectations and raise them simultaneously. The term’s literalness is downright euphoric, a prime example of mundanity in celebration of, in service of, spectacle.

The literalness of “Wunderkammer” is splendid specifically because it frames something so transitory: moments of wonderment that are, by definition and purpose, transient, short-lived.

The less literal, and therefore more truthful, translation is “cabinet of curiosity,” and that particular comprehension—a collection of peculiar things, things that by definition might be considered to exist as refutations of confinement to category—serves Paolo Salvagione’s ends.

In ONE FOR EACH, he has produced a sensory Wunderkammer. His elegant cabinet of curiosities contains five drawers, one for each of the human senses. ONE FOR EACH exists as a compact set of drawers, a box of English buckram and black leather, nearly 250 cubic inches of sensory activity. Each drawer holds a distinct, self-contained object—and in the playful manner that routinely characterizes Salvagione’s work, the senses mingle in unexpected ways:

Three-dimensional projections emphasize the tactile nature of printed images; they embrace the mundanity of a universe ever so slightly apart from our own. Silhouettes of leaves ask you to gauge species by contour, yet the absence of color brings attention to the visual; they play on memory, serving up blank form as screens onto which one projects associated images. Talking tapes acknowledge a tangible aspect of sound; they ask just how much data, how much meaning, can be condensed in simple plastic. A musky, smell-based exploration summons up mental images of physical activity; it dissociates exertion by engaging with the clinical. A unique taste enhancer promises to temporarily bond to your receptors, making all things sour seem sweet; first, however, your fingers must negotiate the brittle blister pack.

And all, in combination and individually, show how our senses can deceive us, and in the process yield something akin to a child’s surprise at the roles these senses play in helping us navigate the world.